Biblical Studies: Material Culture

From the blog

My recent posts have focused on the biblical text and ways to access it online. Here I will turn to the material culture from the ancient environs in which the Bible developed. My focus is oriented more toward resources for digital publication and teaching. I will highlight a select few sites with great resources for bringing the Bible’s ancient environs more to life, as well as some ideas for using the material you find there.

The number of resources for accessing realia of the ancient world online is both substantial and increasing. Nonetheless, I am consistently surprised by how few people incorporate them into their courses and presentations. More shocking is the degree to which educators fail to appropriately source and cite the digital images and resources in their materials. Ultimately, it makes sense to access images or other resources from those who house them without relying on sources like Wikimedia Commons. I don’t mean to disparage Wikipedia or Wikimedia Commons (in fact, this Wikipedia site on artifacts related to the Bible provides an excellent overview of relevant artifacts). But why use that when you can incorporate resources from their original online repositories without any penalties or difficulty?

Reliable sites provide descriptions of how to use their digital objects. Usually, it is as simple as referencing the owner of the copyright. Honestly, academics should model appropriate behavior regarding intellectual property and demand that students and colleagues follow the established legal norms. The best way to do that is by example.

After that homily, let’s consider some digital resources to bring the relevant material culture closer and how to incorporate these into our work. I will mention two types of media here. First, the most obvious: digital photography.

Many museums have begun placing images and descriptions of items in their collections online. Often these are topically oriented, making finding relevant artifacts easy. The Louvre houses an important collection of artifacts from the ancient Near East, with highlights compiles here. This collection contains, for example, a site about the Mesha Inscription including a photo. The photo can be easily embedded in a website or blog by directly linking its URL instead of downloading the photo and uploading it to your site’s server. (Accessing the URL require right-clicking the photo to open it in a new browser tab.) Here’s the image, embedded via its URL:

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Mathieu Rabeau.

Don’t forget to cite the source when embedding!

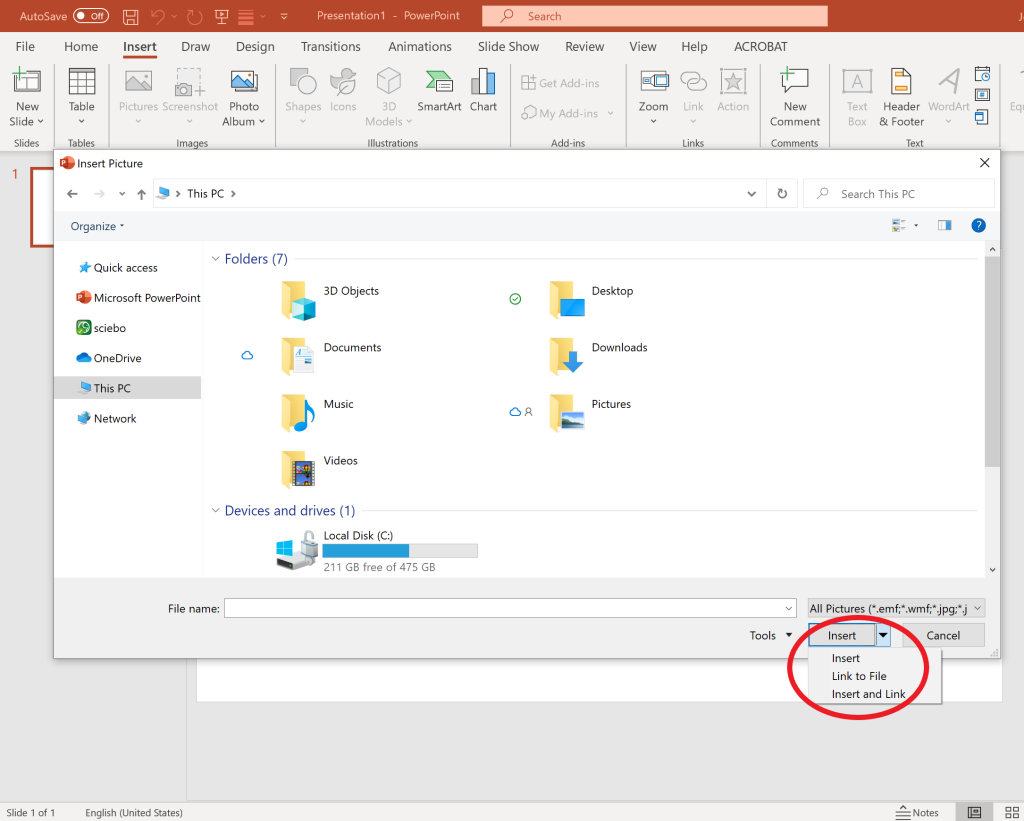

Embedding the URL makes using it a cinch. This method also works to insert images into PowerPoint presentations. In PowerPoint, clicking on the “Insert” ribbon, the “Pictures” button, and then “This Device…”, opens a dialogue box. In the “File name” query you can paste the image’s URL. Then click on the arrow next to “Open” and select “Link to File.” Hitting Enter/Return should add the image to the PowerPoint.

Inserting and Image via URL in PowerPoint.

Reducing the presentation’s file size is the upside, but there are two downsides: displaying the image while presenting requires an internet connection and changes to the link could remove or replace the image. To assuage these issues, use “Link and Insert” instead of “Link to File.” This will embed it in your presentation, but increase the file size of the presentation. However you link it, don’t forget the correct citation!

The most obvious place to look for resources related to the material cultures related to the Bible is the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. They have compiled a ready resource for anyone interested in the intersection of “Archaeology and the Land of Israel,” that extends from the paleolithic period to the Islamic era and the crusaders. Again one finds links to images of the individual artifacts that can be embedded, like these orthostatic lions from Hazor (again, linked via URL).

© The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

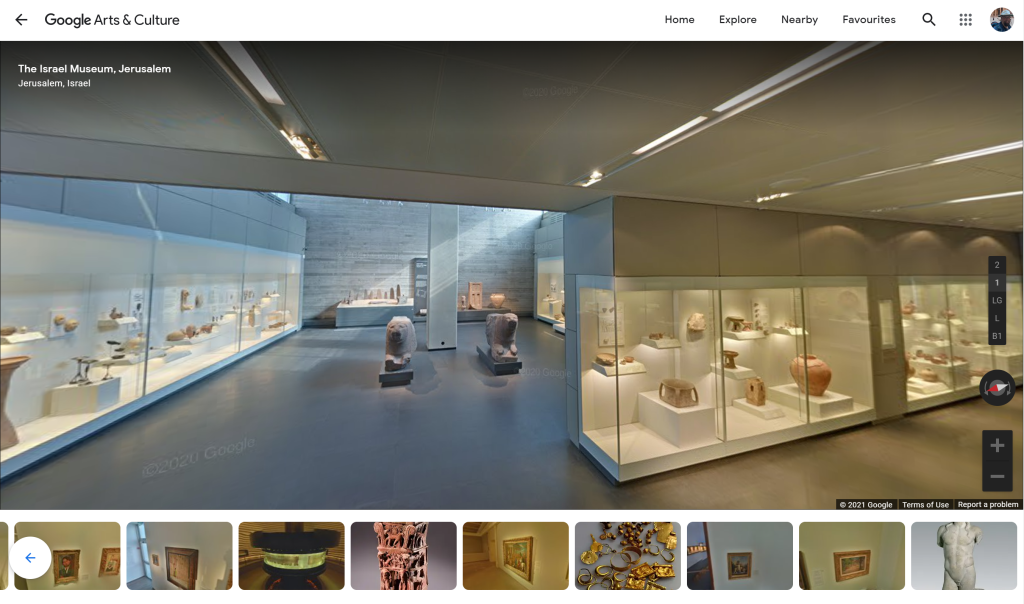

However, there is a second method of viewing materials in the Israel Museum. You can virtually tour the Israel Museum with an internet browser or through the “Arts and Culture App” produced by Google (available in the Play Store). Using these, you can view the artifacts virtually as presented in the museum. Both versions are touch-screen compatible and the app uses the device’s gyroscopes to make the experience more immersive. Viewing artifacts as in the museum can provide more background and contextualize items among culturally or chronologically cognate artifacts. For example, the aforementioned lions from Hazor can be found surrounded by other pieces from the Bronze Age (only when viewed in the this way does the reference to “the one on the left” on the image’s page make any sense).

Screenshot: The Hazor Lions at the Israel Museum virtually.

The British Museum provides similar features on its website and in the “Arts and Culture” app. The website provides first-rate images of numerous objects with easily accessible copyright and usability information linked to each images. For access, click on “Collection” on the homepage and then search for the object. Searching for the “Cyrus Cylinder,” for example, leads to the beautiful image below. Clicking on the link “Use This Image” in the bottom-right corner of image’s page leads to a page with download options and information about using the image.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

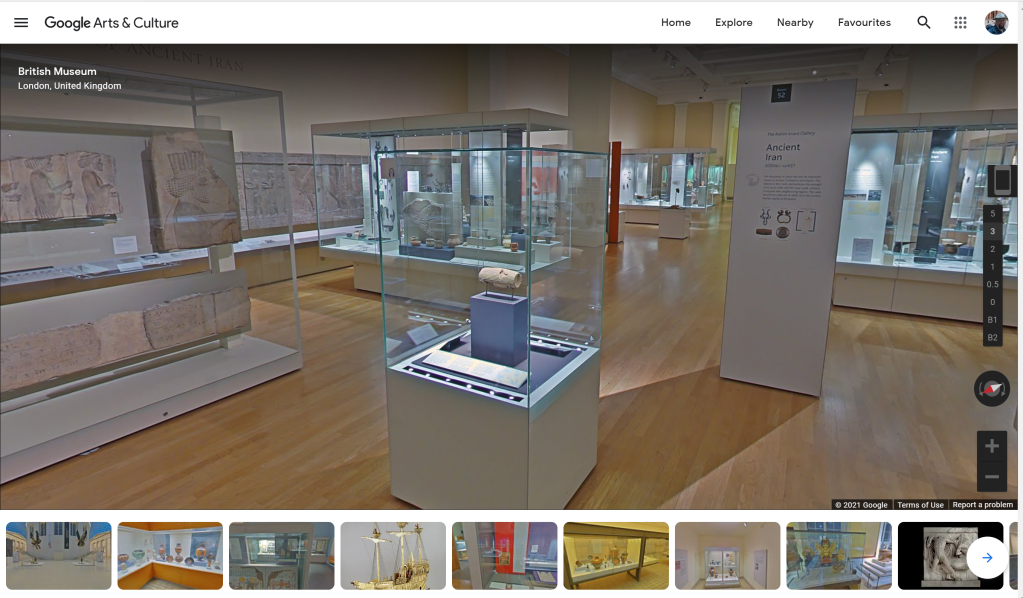

Touring the museum digitally can be used as a fun break or reward within courses. In my recent gamified course on Israel’s history, students could unlock bonus content, including a virtual scavenger hunt for relevant items in the British Museum. Below, one sees what the Cyrus Cylinder looks like in that context, a context with more information about ancient Persia and its culture.

Screenshot: The Cyrus Cylinder, at the British Museum virtually.

Finally, I would like to mention the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem. Their website provides access to a closed temporary exhibit, By the Rivers of Babylon, with interactive elements. This preserves the exhibit and makes it accessible to visitors in spite of its having concluded. (A permanent exhibit that now features much of it remains unavailable online.) This presentation thus overcomes both geographical and temporal limitations, opening the experience to a wider audience for a longer time. However, the Bible Lands museum does not provide access to photos of their collections and is, like the Louvre, not available in the “Arts and Culture” app.

I hope you find these resources and ideas helpful. I’d love to hear your ideas as well!

Cover Image: The Cyrus Cylinder.© The Trustees of the British Museum. (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).